Present day Holland is quite a nice country. Civilized, tolerant, rich,

peaceful: European civilization at its best. Few remember that in XVII century

Holland built a vast colonial empire with sword and fire. While at home they

were fighting a long, bloody war of independence against the Spanish armies,

the Dutch threw themselves into the conquest of the seas. In Asia they

overwhelmed the Portuguese and secured the control of the Indian Ocean and of

the spice trade. In Africa they built fortresses and trading posts along the

coast and they became the main slave traders. In America they were the first to

colonize Manhattan, occupied several Caribbean islands and some mainland

territories and acting as middlemen they almost monopolized the trade among the

English colonies and between the colonies and Europe. Their merchant fleet was

by far the largest in the world and Amsterdam was the center of world trade and

finance. And of sugar refining.

At the beginning of XVII century, Holland was the richest and the most

modern and technologically advanced country all over Europe. The Dutch were also

the pioneers of commercial distillation onalarge scale, we already

know that the very word brandy is

thought to derive from the Dutch gebrande

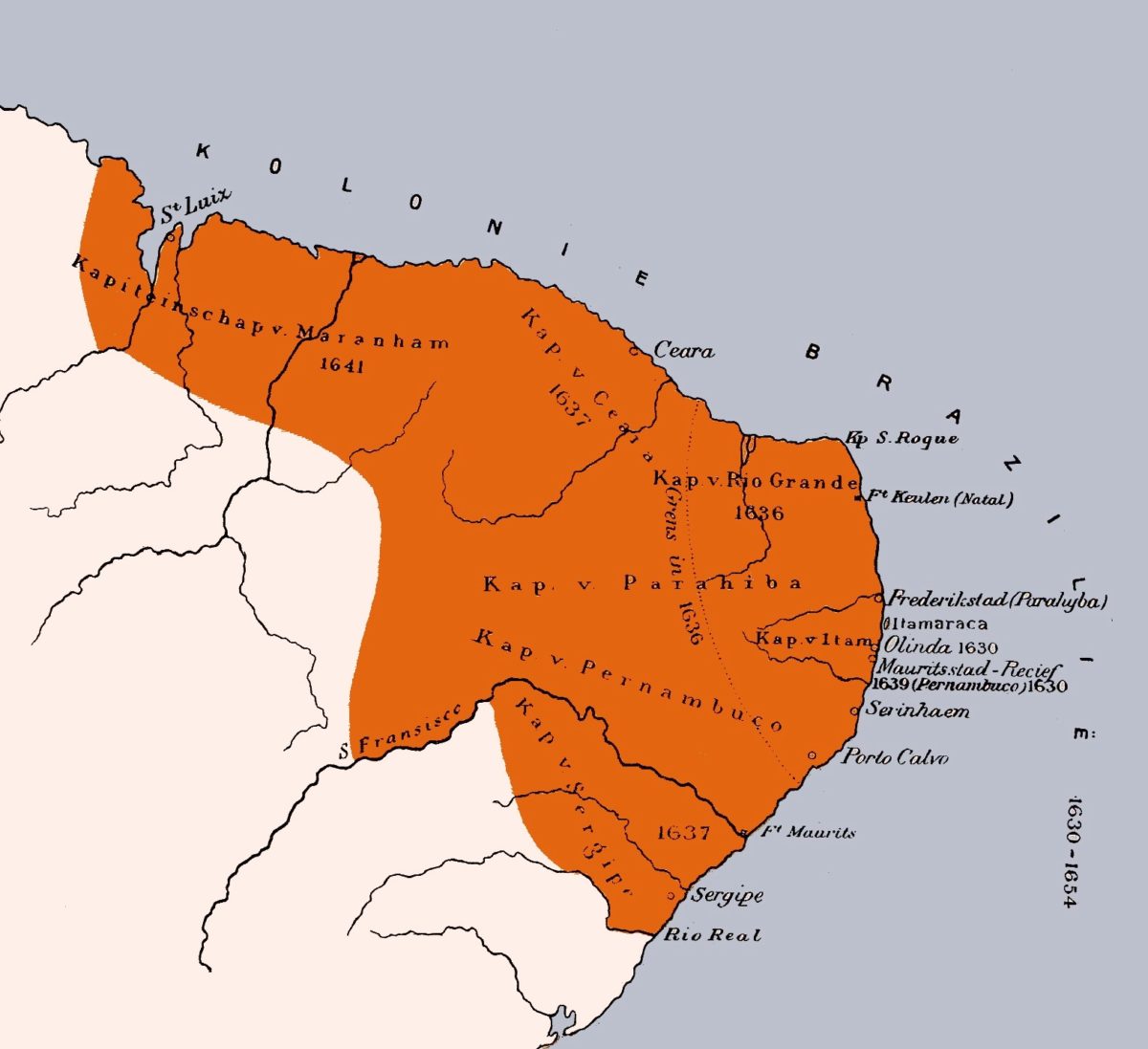

wijn. In 1624 the Dutch West India Company occupied the coastal region of

Pernambuco, now Recife, in Brazil, then part of the Spanish Empire. Pernambuco

was a great producer of sugar and after the military occupation the Company

made great investments, bringing from Holland men, capital, technical skills,

equipment.

In 1638, Georg Marcgraf and Willem Piso arrived in Pernambuco to join the

brilliant entourage of the new Governor, Count Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen.

In spite of their youth, both were already renowned naturalists. The older of the

two, Marcgraf, was born in 1610 in Liebstadt, present day Germany. In his

university years, he had studied mathematics, medicine, botany and first of all

astronomy. The Count built for him a real observatory and, for his astronomical

observations, he was later called the First Astronomer of the Americas. The

younger Willem Piso was born in Leiden, Holland, in 1611. He had studied

medicine in France, then had returned to Holland and joined the circle of the

great geographer and humanist Johannes de Laet. Today he is considered one of

the founders of tropical medicine. During their stay in Brazil, they

participated in many long excursions to collect samples from near and far.

Sometimes they were escorted by Dutch military officers, sometimes they joined

the Brazilian and Tapuyas military raids against enemy Indian groups.

They discovered animals and plants, drew maps, made extensive observations

of nature and also of the men inhabiting it. They also made use of the scientific institutions that the Count had

built in Recife: a zoo, a botanical garden and a museum. The huge amount of

information they gathered enabled them to write the first systematic study of

American nature. Marcgraf wrote his notes in a personal, secret language that

others could understand only with great difficulty. Probably, he meant to

translate his notes when he got back to Holland, but he died in 1643, in Angola

while he was drawing a map of the Dutch settlements there. Piso, on the other

hand, returned safely to Holland and continued to practice and study medicine.

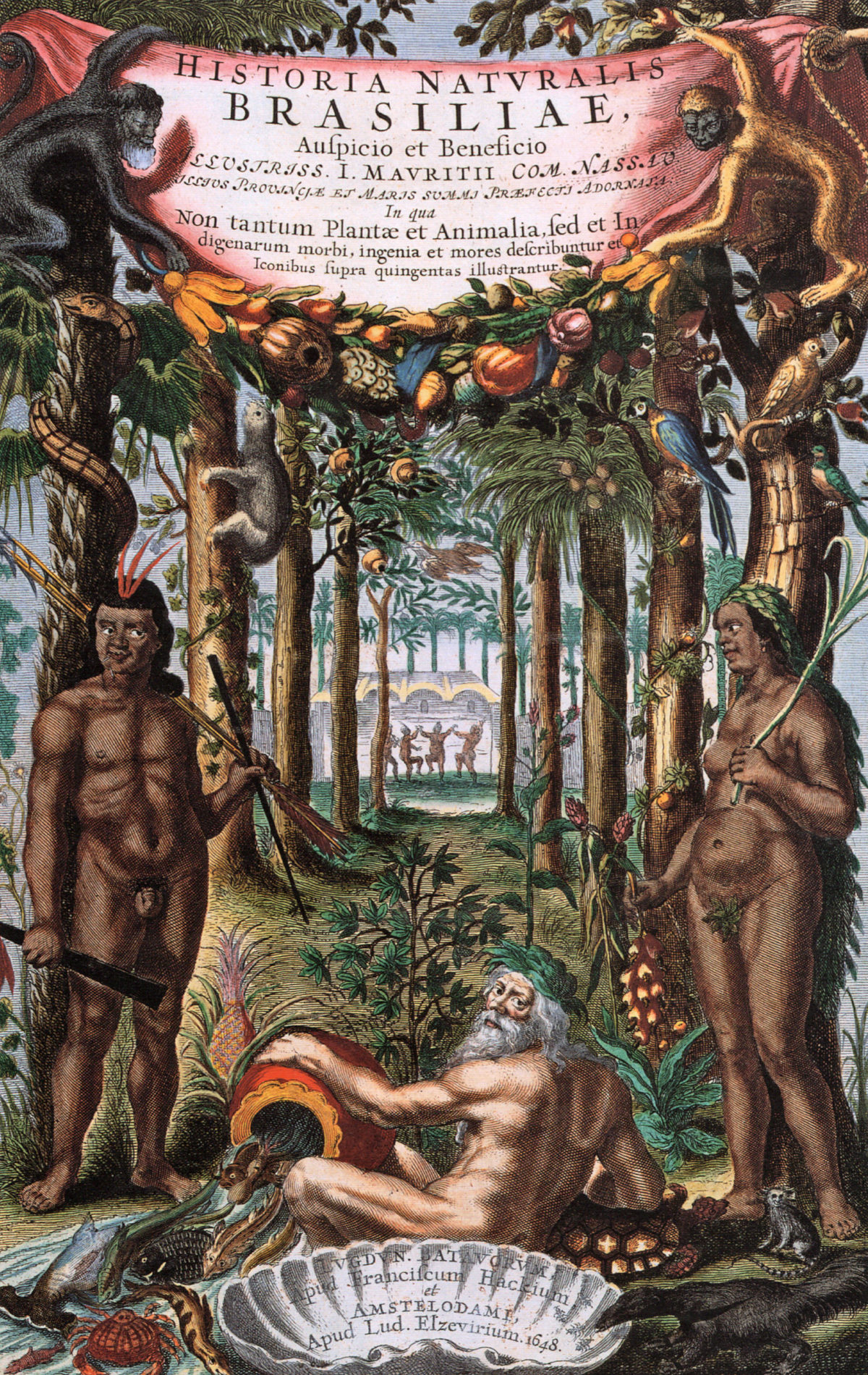

Marcgraf’s notes were translated, ordered, united to Piso’s ones, and published

in Latin by Johannes de Laet in Amsterdam in 1648 under the title of “Historia Naturalis Brasiliae”, Natural

History of Brazil. Latin was the

common language of cultivated people of the age, the Republic of Letters, and

the book had a big and lasting success, possibly because, from the very

beginning, the authors emphasized their own direct experience in Brazil and

their great efforts on the field, unlike the many armchair natural historians

who never visited the New World and wrote their books at home in Europe, on the

accounts of some travelers.

Why am I speaking about an old, half-forgotten book written in Latin?

Because in this book I found the historical evidence that in Dutch Brazil they

commonly distilled a strong spirit from sugar cane.

Let’s see in detail. “Historia

Naturalis Brasiliae” devotes a whole chapter, written by Willem Piso, to

sugar. Hardly surprising, since the Dutch had gone to Brazil mainly to take

hold of its precious sugar. But, like many of his contemporaries, Piso is also

struck by the complexity and sheer spectacle of sugar making. At the time in

Europe there were hardly any big factories. Manufacturing took place in many

small workshops where often a singlemasterworked leisurely, assisted by few

apprentices. In sugar factories, on the other hand, during the harvest, “night

and day tongues of fire rise up, terrible in their blaze”, around which scores of black, half-naked, sweating men bustle in

a frenzied way. The sugarcane is unloaded from the carts, cleaned, cut and

squeezed. And the juice gathered is boiled in the cauldrons. All in quick,

rigorous succession and hurriedly, breathlessly … a hellish scene, a veritable “Tropical

Babylon”, as a contemporary author wrote.

Piso had first to understand himself what he was seeing, and it was not so

easy. Then he had to explain it to his European readers. And he had to explain

it in Latin. But the ancient Romans, whose language he wrote in, did not know

sugarcane, sugar factories, sugar, stills, distillation or spirits. It was

therefore necessary tointroduce new

words into Latin, such as caldo for

the juice of the cane. Or bend old words, born in an entirely different

context, to make them express a new meaning; so, vinum, wine, becomes a general term for every alcoholic (fermented)

beverage.

After describing how sugarcane was squeezed and the caldo collected, Piso writes: “Thence, mixing some water with it, they make also a wine, popularly called Garapo: local people ask for it greedily and on it, if it is aged, they get drunk. …So, from this first liquid (that is, the caldo), sugary wine, vinum adustum,acetum, cooked honey and sugar itself can be prepared.”

Let us give a good look at this list.

Sugary wine is the Garapo,

that is the fermented beverage made from sugar juice (and maybe also from

molasses), a word with a long History in Latin America, see for instance modern

Spanish guarapo.

Acetum (vinegar) is the raw juice of the cane mixed

with water. We know that after a few days it went sour and was used in

medicine.

Cooked honey is molasses. I am not an expert of philology

(sad to say), but it is likely that the English word molasses came from the

Spanish melaza or the Portuguese melaço, based respectively on the words miel and mel, honey.

And, of course, sugar is sugar.

So, what is this vinum adustum?

The literal translation is “burnt wine”. Evidently, it was another beverage,

besides Garapo, that was obtained

from the sugarcane. A beverage which was made by burning the Garapo itself. And maybe this is what

Piso refers to when he writes “and on it, if it is aged, they get drunk.”

We know that in Piso’s Netherlands a burnt wine was already widespread. It

was made by burning, that is, distilling the wine made from grape juice and it

was extremely strong. It was called gebrande

wijn, better known later as Brandy.

Piso must bend his Latin to describe something which in Latin did not

exist and which is similar to brandy. He is telling us that the fermented beverage

made from the cane juice was then burnt, that is, distilled in a still, as they

did for brandy, resulting in a new beverage, as strong as brandy. He does not

have a specific name for it yet and, basing himself on the production process,

calls it vinum adustum, burnt wine.

But now we can call it by the monosyllabic power of its modern name: Rum.

So, now we know that in Dutch

Brazil they produced rum. But there is more. Reading Piso’s description carefully

it is evident that this new strong beverage was, in Dutch Brazil, something

commonplace, locally well-known and widely-spread. It is hard to think that it

was a recent invention of the just arrived Dutch. Moreover, all the sources of

the time confirm that the Dutch were not skilled in the growing and processing

of sugarcane, which they left largely in the hands of the Portuguese landowners.

So it is reasonable to think that it was the Portuguese who started the

production of this new beverage, before the arrival of the Dutch.

It is easy to recognize that the conclusions

of this research are consistent with Prof. Azevedo’s essay. To sum up, thanks

to the documents quoted by Prof Azevedo and in accordance with his analysis,

and with the help of a careful reading of Piso’s part of the “Historia Naturalis Brasiliae”, we can

conclude that Brazil is the real birthplace of Rum. And that its birth happened

probably at the beginning of XVII century.

Marco Pierini

PS: if you are interested in

reading a comprehensive history of rum in the United States I published a book

on this topic, “AMERICAN RUM A Short

History of Rum in Early America”. You can find it on Amazon.