A few years ago, I formulated the hypothesis of the Dutch/Brazilian origin of rum which I described in my previous articles, by speculating on what Richard Ligon writes.

But Ligon was not enough. So I read many other books about Barbados, the West Indies and rum trying to unearth further proof. And I have found plenty of leads, but they are clues rather than conclusive evidence.

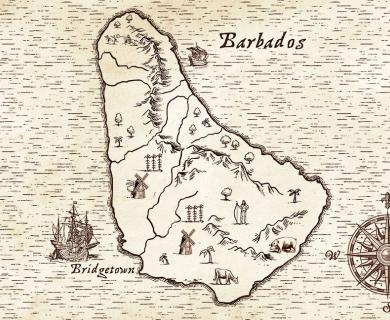

And I decided to go to Barbados to continue with my research.

The thing is that very few have carried out real historical research on rum and noone, as far as I know, on its origin.

On the one hand, most of the books on rum are excellent books, but not scholarly publications, they are written by journalists and experts, not by professional historians.

On the other, there is plenty of solid historical research on sugar, on the colonization of the Americas, on the Atlantic economy, etc. Very little on rum. So, we must get to what interests us, rum and its origins, by studying books which mainly deal with something else.

In the space of an article I can’t mention all the clues I have found. But you can trust me: (nearly) all the sources underline the importance of the Dutch and of Pernambuco in the English settlement of Barbados and later in the development and production of sugar. And rum was born as a by-product of sugar. But I would like to share with you some of the most intriguing ones, though.

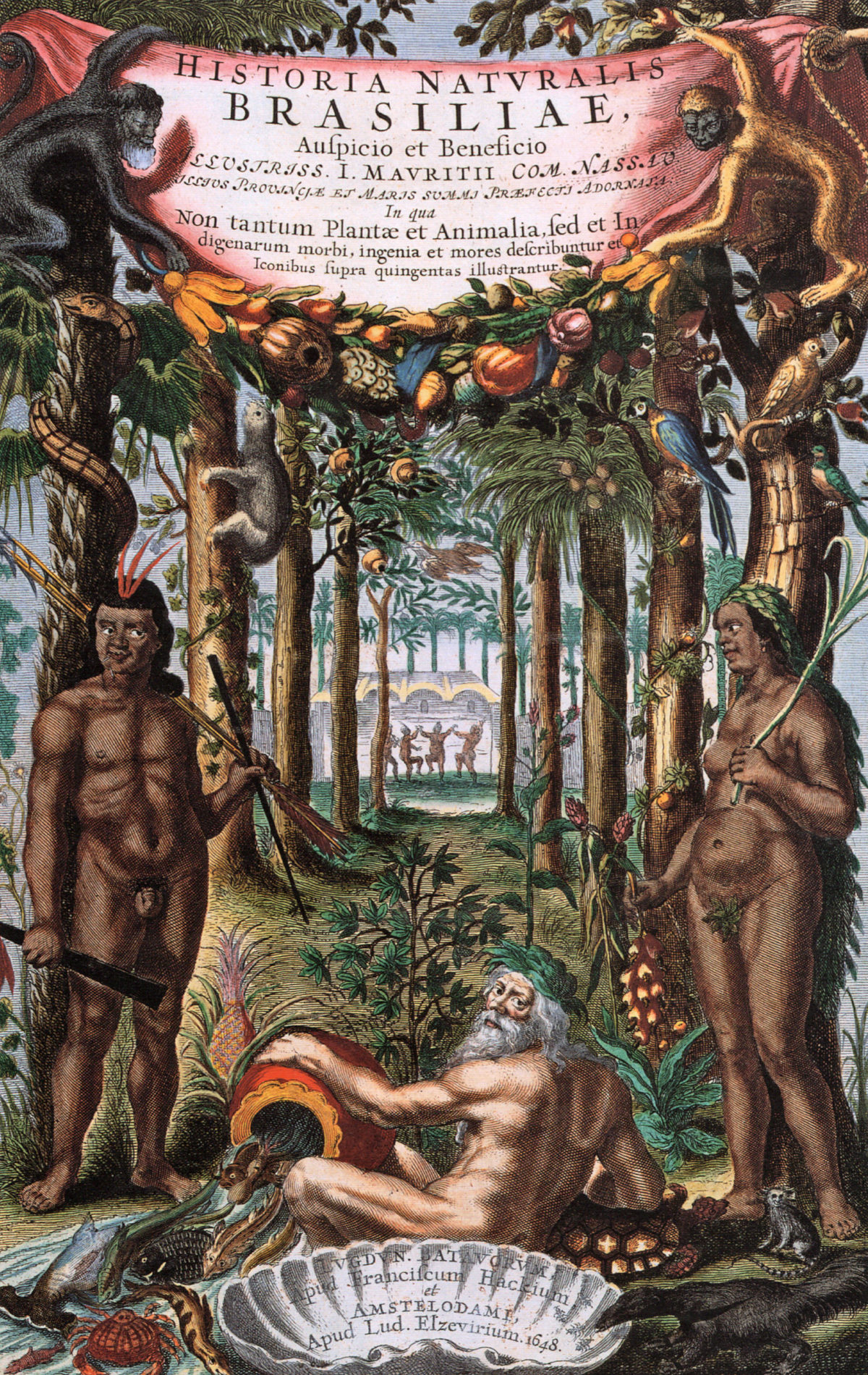

“Some Dutch vessels, which were specially licensed by the court of Spain to trade to Brazil, landed in Barbados on their return to Europe, for the purpose of procuring refreshment. On their arrival in Zeeland they gave a flattery account of the island, which was communicated by a correspondent to Sir William Courteen, a merchant of London, who was at that time deeply engaged in the trade with the New World.” So writes Schomburk’s in his classic History of Barbados, published in London in 1847. It is worth remembering that Sir William Courteen is the merchant who promoted and financed the first English settlement in Barbados. And then: “It is asserted that previous to the revolution the Dutch possessed more interest in the island than the English, which they gained by their liberal spirit in commercial transactions.” The “revolution” is the Civil War which brought to power Oliver Cromwell and put an end to the friendly relations between Holland and England.

“The Dutch, their control of the sugar industry at Pernambuco threatened, proved the island’s salvation. They taught the Barbadians how to grow, harvest, and process sugarcane, loaned them the capital to build plantations, sold them the slaves to do the work, shipped the product across the Atlantic, and marketed it in the major European trading centers.” This is what Russell R. Menard, the well- known economic historian, wrote in 1993.

In Barbados I also visited the Synagogue and the Jewish Cemetery and the adjoining Museum, solid evidences of the historic importance of Jews in the Caribbean. I also bought a little book, Monumental Inscriptions in the Jewish Synagogue at Bridgetown Barbados.

In the Introduction, among other things, we can read:

“[…] the founder of the Bridgetown Synagogue, Joseph Jessurum Mendes, alias Lewis Dias, was active in the Pernambuco (Recife) Synagogue from 1649 to 1652”… .

Marco Pierini