Fifteen men on the dead man’s chest-

Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!

Drink and the devil had done for the rest-

Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!

Maybe it is different today, but all the boys of my generation have read, and dreamt on, these uncouth lyrics which the mysterious “Captain” sings in Robert L. Stevenson’s “Treasure Island”. I have to admit that I felt a bit of emotion picking it up again in order to write this article; emotion and nostalgia, casting my mind back over the hours of sheer bliss that this book gave many, alas, too many years ago.

Published in 1882-3 the novel had an immediate, great and lasting success and paved the way for the enduring association between Rum and Pirates. An association later fostered by novels, fairy tales, movies and many stories, from Disney’s Captain Hook up to Jack Sparrow, passing through very romanticized historical figures such as Captain Morgan and Blackbeard. So, today in popular culture rum is associated with pirates and there are a lot of rum brands, labels and ads which draw inspiration from them. In the Rum World too, our spirit is often called the true Pirates’ Drink. Therefore, a Rum Historian cannot avoid dealing with pirates. I have procrastinated a lot, but I think the moment has arrived.

Many readers may be surprised, but, as a matter of fact, in the Golden Age of Caribbean Piracy, in the 1600s, rum was not usually consumed by the crews of pirates’ ships, trailing far behind brandy and wine. It is only during a later phase, in the first half of the 1700s, that rum emerged as these new pirates’ favorite beverage.

The most famous of the pirates and “privateers” – who unlike other pirates were acting under the cover and with the support of European governments through a so- called letter of marque – that infested the Caribbean during the Golden Age of Piracy is probably Captain Henry Morgan.

Born in Wales in 1635, he arrived in Barbados probably as an indentured servant, the lowest rank of the white settlers. In 1655 he left his work, actually probably escaped, – like many other indentured servants – to join the English Fleet that called in Barbados in late January 1655. It was a big fleet: 37 men-of-war and 3.000 soldiers under the command of Vice-Admiral William Penn and with General Robert Venable in charge of the army. Its purpose was to attack and conquer the large Spanish island of Hispaniola, present-day Santo Domingo. It was not another privateer enterprise, but something new and bigger. For the first time England attempted to conquer and hold the colony of one of its European rivals: Oliver Crowell’s ambitious “Western Design” was on the move. After a short stay in Barbados, at that time the most important British base in the Caribbean, to embark provisions and more troops, among them many indentured servants that wanted to flee the island, it moved to Hispaniola. There the fleet landed the army to attack the town of Santo Domingo. The attack was ill prepared and the reaction of the Spanish was strong and effective. After a crushing defeat, the English troops retired in disarray and had to re-embark quickly.

Worried about having to return home defeated and with empty hands, in May 1655 Penn decided to attack Jamaica, at that time a small, poor Spanish island, sparsely populated and virtually undefended. This time the amphibious attack was prepared with care and it was a success, Britain took possession of Jamaica, but this did not appease Cromwell that was devastated by the Hispaniola disaster to the point to fell ill and sent Penn and Venable to the Tower.

The English conquest of Jamaica, on the contrary, made the fortune of Morgan. The Governor of Jamaica granted him a letter of marque and for years Morgan scourged /the Spanish ships and possessions in America, becoming notorious for his cruelty, but also rich and powerful, with a large following among the pirates’ crews. The English Crown rewarded him with a knighthood and with important political positions.

According to W. Curtis in his seminal and pleasant book “And a Bottle of Rum: A History of the New World in Ten Cocktails” 2006, “What we know about Morgan’s exploits is chiefly due to a remarkable account published by a Dutchman who wrote under the name of Alexander Exquemelin. He spent eight years with the pirates in the Caribbean, a large part of that with Morgan. His 1678 book, De Americaenshe Zee-rovers, was translated into English and published in 1684 as Bucaniers of America, and proved as enduring as it was popuar. Although riddled with inaccuracies and exaggerations, Exquemelin’s lavish account is considered the best source of information on Captain Morgan and the habits of pirates. The detail in Exquemelin’s book is so rich and so lavish that it grieves me slightly to make one observation. At no time is rum ever mentioned.”

The reason is quite simple: the pirates plundered mainly Spanish ships and colonies, where rum was not then widespread. Although around the middle of the century rum was already drunk in Barbados, it was not widespread in the Spanish empire. Despite the presence of many sugar cane plantations, the Spanish Crown prohibited it, for there had been an effective lobbying strategy carried out in Spain by wine and brandy producers, who were terrified by the competition that cheap colonial rum could do to their products; so the Spanish government decided to enforce a substantial ban on the production of rum and almost any other alcoholic beverages in America. In the Spanish Caribbean, rum was produced clandestinely and in limited quantities for the local market, but people mainly drank wine or brandy imported from the motherland, drinks that also met the taste of the Spanish colonists more than rum. As a consequence, when a Spanish village or ship was attacked and looted by Morgan’s pirates, they would find – and drink – mainly wine and brandy, not rum.

The pirates of this age could drink rum when, after a period spent raiding and pillaging, they returned to Jamaica or to other islands controlled by the British to spend on alcohol and women what they had extorted from the unfortunate Spanish settlers. But it is probable that, until they ran out of money, they preferred more expensive and prestigious drinks like wine. When telling the story of Captain Morgan and his crew, pirates’ chronicler Charles Leslie writes that “Wine and Women drained Their Wealth to such a Degree That in a little time some of them Became reduced to beggary. They were known to spend 2 or 3000 Pieces of Eight in One Night; and one of them gave a Strumpet 500 to see her naked … Morgan found many of His chief officers and soldiers reduced to Their former state of indigence Through Their immoderate vices and debauchery “. They would then ask him to go raiding again” Thereby to get something to expend anew in wine and strumpets”.

Actually, pirates were not particularly selective about the type of alcohol they consumed. In the eyes of a modern observer it seems that taste did not play any role in determining if the pirates preferred to consume a type of alcohol over another. They drank in order to get drunk, not for the pleasure of drinking. Their life, as often the one of their victims, was hard and dangerous, and in alcohol they sought a fleeting oblivion. Therefore, they would drink – or, to be more realistic, would swallow – any type of alcohol with exactly the same insatiable thirst, to an extent which is incomprehensible to us living in the 21st century.

Here is an interesting and colorful anecdote: in 1671, during the march of Morgan and his men to Panama City – which was to be followed by one of the most tragic pages in the history of the city – “… fifteen or sixteen jars of Peruvian wine were uncovered in one village along the way. The men fell upon it ‘with rapacity’ and consumed it without pause. No sooner was the wine emptied than the drinkers Began vomiting copiously. That suspecting the wine Had Been poisoned, the soldiers sat back moaning and awaited their grim fate. Remarkably, no one died. Exquemelin suspected that was the reaction from drinking too hastily on very empty stomachs”. (Curtis)

It is only later, during the early 1700s, that rum spread everywhere in the Americas, and consequently it is only in that period that pirates started drinking rum on a daily basis. Among the English pirates no one represents this combination better than the infamous Blackbeard. He had taken his first steps as a “privateer” during the Spanish Succession War – 1701 to 1714 – and became a pirate when, after the peace treaty, the English crown no longer needed his services. Tall and robust, with a black beard so impressive that it became his nickname, Blackbeard was so fond of rum that his passion was legendary even among his contemporaries, who were accustomed to a high alcohol consumption standard. His biographer Robert Lee writes that: “Rum was never His Master. He could handle it as no other man of His Day, and he was never known to pass out from an excess.” Among other things, Blackbeard was also known to consume a terrifying cocktail made with rum and gunpowder which, writes Curtis, “he would ignite and swill while it flamed and popped.” I don’t know whether that’s really true, maybe it was a Fire-eater trick, but certainly it must have been impressive and very useful for creating his own myth.

Blackbeard’s contemporaries report that he and his crew lived perpetually almost in a state of drunkenness, but this apparently did not weaken their skills as sailors and pirates: it is reported that in eighteen months they managed to capture up to twenty ships. Not only was the abundance of rum on board not a discipline problem, on the contrary, its absence was! Blackbeard himself once wrote of a predicament in his ship’s log: “Such a day, rum all out: – Our company somewhat sober: – A damned confusion among us!” He was even worried about a possible mutiny of his crew, until they sacked a ship carrying “a great deal of liquor on board, I kept the company hot, damned hot; then all things went well again.”

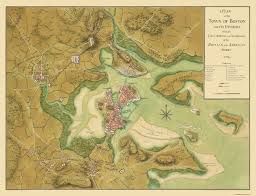

His skill as a pirate and his cruelty made him quickly become the most feared pirate of his time. This not only increased the number of his followers – in 1718 he had come to command a fleet of eight ships, and this despite having commanded its first ship only in 1716! – but also of those who wanted to free the seas from a similar plague. The Governors of the English colonies started gathering all their resources to eliminate Blackbeard from the seas: after his refusal of an amnesty (which implied his immediate withdrawal from pirating) on July 20, 1718, the Virginia Governor ordered Royal Navy Lieutenant Maynard to capture Blackbeard, dead or alive. Sailing on a ship called “the Pearl”, Maynard reached Blackbeard on November 21, 1718, in the inlet of the Ocracoke island (North Carolina) that the pirate used as a base; when the two ships met, Blackbeard gave the order to board, not realizing that the bulk of Maynard’s men was still below deck: the fight was very hard, and it is reported that Blackbeard himself managed to disarm Maynard, but he then ended up being surrounded and massacred by British soldiers, after which his men stopped fighting and surrendered. It is said that Blackbeard did not die before he was wounded twenty-five times – including five gunshots – and that when his body was thrown overboard it circled around the ship for three times before sinking.

The story of Blackbeard’s death and the amount of anecdotes that circulate about it gives the measure of how the character of Blackbeard had become a legend: he is not only the most famous pirate since the times of Morgan, but also represents the swansong of an era in which piracy dominated over the Atlantic. The British Navy was becoming more and more powerful, and in order to secure trade’s main routes, the control it held over the seas and coasts was strengthened. With his death it was clear that, even though many more years were needed to finally eradicate it, piracy had already seen its best days.

Marco Pierini

PS: I published this article on January 2022 in the “Got Rum?” magazine. If you want to read my articles and to be constantly updated about the rum world, visit www.gotrum.com