Now I have to say some words about the relation between cachaça and rum. I am aware of the efforts of Brazil to defend and promote cachaça as a national product, with its own characteristics, different from rum. And I think that it makes sense to defend the originality of cachaça in today’s world market. But as regards to History, cachaça and rum are the same product: a distilled beverage whose raw material comes from sugar cane.

However, for the sake of completeness, it is fair to say that there is quite a different story circulating in the Rum Community (the net of websites, books, festivals, experts and aficionados) about the origins of cachaça. It usually begins in 1532, when the Portuguese started to cultivate sugar cane in Brazil. Some say that the distillation of sugar cane products began almost immediately, others few decades later. Someone adds that the Portuguese learned distillation from the Arabs, others stress that in contemporary documents the word “cagaza” or something like that, can be found. Therefore, the origins of rum would appear to be almost a hundred years before what I indicated.

As often happens, this story is bouncing off from books to websites, from websites to festivals, and the other way round. And for the sheer fact of its diffusion, it is growing in prestige and authority. But its sources are not clear. Some do not quote any sources at all, others quote not clearly identified written documents.

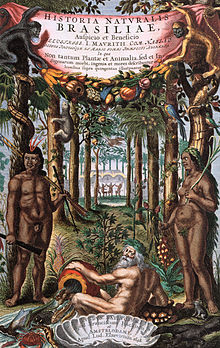

But in order to predate the origins of rum back to round 1550, we need reliable sources provingthe early distillation of sugar cane products. And these sources can only be of two types: archeological finds (stills) or written texts of the time. For instance, “Historia Naturalis Brasiliae” is one such source. No one, as far as I know, quotes archeological sources and the references to contemporary written texts are vague. Moreover, documents written in the Portuguese language of the XVI Century are not easy to understand, because, like English, Portuguese has changed greatly over these 500 years and the meaning of the words is not always clear to us. Actually, we find the word cachazo or similar in many documents of the XVI century, but during most of the colonial period, the word cachaça was commonly used for the foam of the cauldrons where sugar cane juice boiled, and not for the spirit.

Moreover, we know that commercial distillation was not common in Europe before the second half of 1500, andit is unlikely that in Brazil it should have happened earlier.

Therefore we have to conclude that the story which places the origins of cachaça in Brazil before or round 1550 is as yet unfounded. If in the future someone discovers new, trustworthy, sources about early distillation in Brazil, I will be happy to change my opinion but at the moment I must confirm that the earliest commercial production of rum took place in Brazil only at the beginnings of the XVIIcentury.

Marco Pierini

PS: if you are interested in reading a comprehensive history of rum in the United States I published a book on this topic, “AMERICAN RUM A Short History of Rum in Early America”. You can find it on Amazon.