What is rum? Rum is a

strong alcoholic beverage made by the fermentation and then by the distillation

of the products of sugar cane: cane juice, molasses, skimmings etc.

It may be useful to remember that

fermentation is the process by which microorganisms called yeasts feed on

sugar, releasing alcohol, gas and heat. Fermentation is a natural, spontaneous

process: for example, when fruit rots it often ferments.

It was later gradually

improved by men for their own ends, let us say that it is a relatively easy

thing. When

America was discovered, in Europe, Asia and Africa the production of fermented

beverages had been commonplacefor thousands of years: wine, beer, etc.

The raw materials of

rum are the coproducts of sugarcane: sometimes sugarcane juice, but mostly

molasses, sometimes even syrups. The raw materials are put into a fermentation

wash, to which water and other

substances are added. Originally, the fermentation would happen owing to the

yeasts naturally present in sugarcane, in the soil, in the air, and so on: it

was a spontaneous process which man was unlikely to be able to influence,

whereas today specifically selected yeasts are used, the whole process is

monitored, by adding or removing nutrients, modifying the temperature, and so

on. The production of alcohol takes place entirely during the fermentation

process.

Alcoholic distillation,

on the contrary, does not exist in nature, it is an artificial process, devised

and realized by men. And it is difficult. The fermented liquid, or wash, is put

into a container, pot-still or column-still, and heated until it boils and

produces vapors. The vapors are then collected, cooled and brought back to a

liquid state. At the end of this process, in the liquid produced, the spirit, there

will be a much lower percentage of water than what was present in the fermented

liquid, whereas the percentage of alcohol will be much higher. We have

therefore produced an alcoholic beverage that is much stronger than any

fermented liquid, which is exactly the desired result. To put it simply,

distillation concentrates alcohol. For the sake of clarity, I’ll say that

again: distillation concentrates the alcohol already present in the wash, it

does not produce it.

According to some archeological

remains the distillation of alcohol was made in present-day Pakistan as early

as c. 150 B.C. and from there it spread later in south-east Asia and China. There

are also some uncertain references in Indian literature that could push back its

origins to c. 500 B.C. But this is not our point here. As far as we are

concerned, it is more or less generally accepted that the history of

distillation starts in the West with the Greeks of

Alexandria before the Christian era. Later the Arab alchemists used distillation

for studies and research of various kinds, and for making perfumes and maybe

also to produce alcohol for medicinal use. In the XII century, it is thought to

have reached Italy at the famous medical School of Salerno, where it was used

to distill wine, creating a new, wonderful beverage, an almost pure alcohol

called in Latin aqua vitae – water of life – from which derive the

Italian acquavite, the French eau de vie and also the Gaelic uisgebeatha,

later whisky. But, as far as I know, the earliest description

of an alcoholic distillation can be found only about a century later. It is

again from Italy, in the book Consilia by

Taddeo Alderotti, a famous physician and scientist who was born in Florence, but

lived in Bologna in the XIII century. It then spread all over Europe,

but usually in limited quantities, quite expensive, that doctors and

pharmacists dispensed to their élite customers. “Est consolatio ultima corporis humani”

(“Last solace of the human body”), Raimond Lull will write later. Anyway, scholars

agree that the first use of alcohol was medicinal.

Over the centuries, all over Europe

people started to produce distilled beverages not only as a drug but also as a beverage

for pleasure consumption. For example we know that in 1514 the King of France,

Louis XII, issued a decree with which he granted the Guild of “vinagriers” (vinegar makers) the right

to distill wine to produce brandy. And this is an important step in the long

process which has transformed distillation from a mysterious activity,

restricted to alchemists and pharmacists, into a mass production for the

pleasure of drinking.

There isn’t a general consensus

among scholars, but it seems to me reasonable to think that large scale

commercial production of distilled beverages meant for drinkers’ pleasure

consumption started in Europe, probably in Holland, in the second half of the

XVI century. Holland was at

that time the most modern and technologically advanced country in Europe and

the very word brandy is thought to

derive from the Dutch gebrande wijn,

which meant, basically, burnt wine. And we know that a John Hester started his “Stillitorie” in London in 1576

with this advertisement: “These

Oiles, Waters, Extractions or essences, Saltes, and other Compositions; are at

Paule Wharfe ready made to be soldem by IOHN HESTER, practisioner in the art of

Distillation; who will also be ready for a reasonable stipend to instruct any

that are desirous to learne the secrets of the same in few dayes”.

The new importance of distilled

beverages is reflected in the foundation of Guilds of distillers. The London Worshipful Company of Distillers was

founded in 1638 and in the same years similar Guilds were born in Paris,

Rotterdam and elsewhere. However, the distillation of wine continued to be

expensive. Even producing alcoholby distilling grain was costly, and it

was dangerous too: cereals were the staple diet of the majority of the

population and harvests were often poor. Therefore, diverting a significant

share of the harvest from food consumption to distillation increased the risk

of hunger and famine. In any case, distillation was seasonal, it was done after

the harvest and before the raw material could deteriorate.

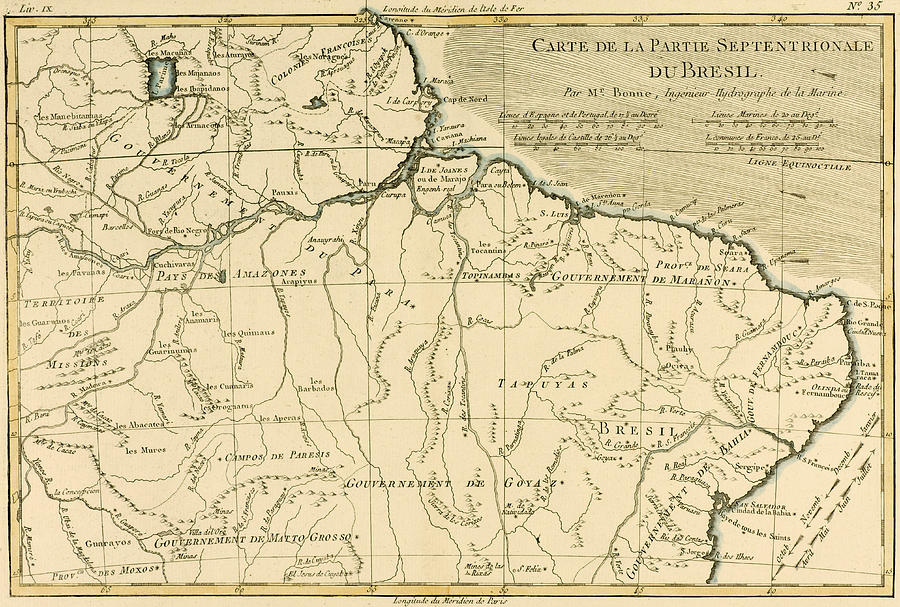

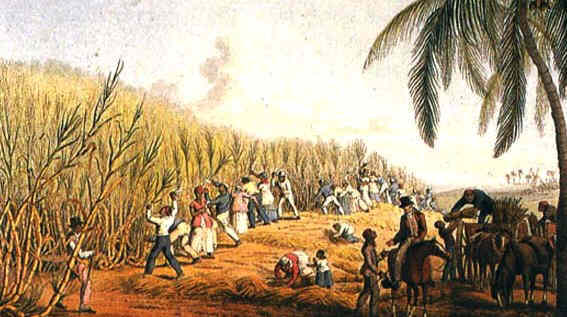

Brazilian and Caribbean sugar

plantations changed the situation radically. Sugarcane provided distillers with

plentiful, cheap raw material. Molasses in particular was extremely cheap:

actually, before it started to be used to produce rum, it was largely thrown

away. Rum, our rum, was born when European distillation techniques met

sugarcane and this meeting took place in the Americas between XVI and XVII

centuries. But where exactly, and when?

We will deal with this issue in

the next article.

Marco Pierini

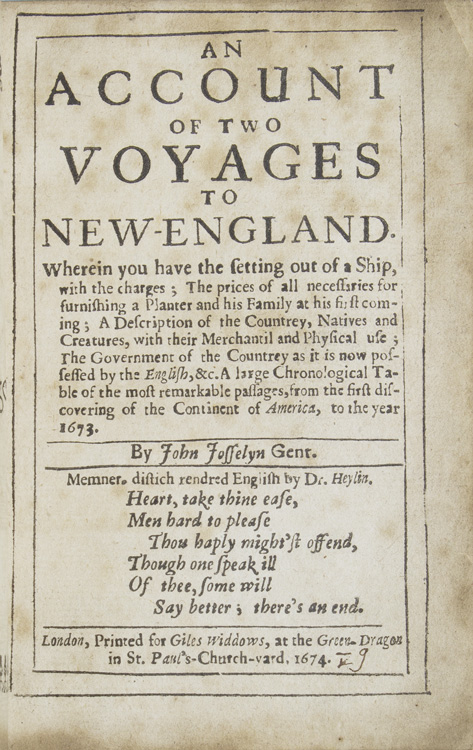

PS: if you are interested in

reading a comprehensive history of rum in the United States I published a book

on this topic, “AMERICAN RUM A Short

History of Rum in Early America”. You can find it on Amazon.

the British Empire, owing to the early, massive diffusion of rum among British people. The very word Rum is generally held to be English, even though its origins are uncertain.

the British Empire, owing to the early, massive diffusion of rum among British people. The very word Rum is generally held to be English, even though its origins are uncertain.